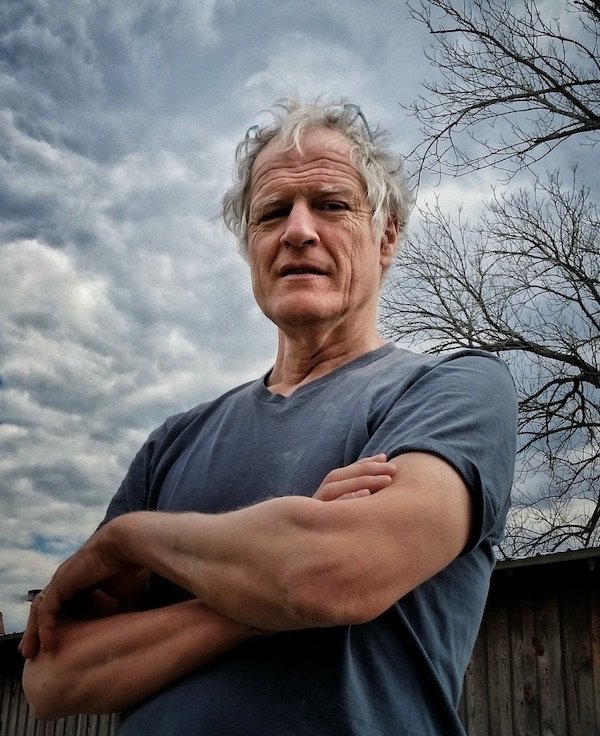

MARK HEWITT ~ ARTIST STATEMENT

Michael Cardew’s idiosyncratic synthesizing of global folk pottery traditions in the service of making sublime useful pots was at the heart of my first apprenticeship. A second, with Todd Piker in Connecticut, and one by proxy with Svend Bayer, equipped me with skills that have enabled me, with help from my wife, Carol, to make a profitable living as a maker of functional pots.

When I moved to North Carolina in 1983 this training made me particularly sensitive to the South’s folk pottery traditions.

Historically, regional utilitarian traditions were enclosed, people learned within narrow parameters, styles were relatively static. In this context, competition between potters and apprentices propelled quality forward. Individualism took the form of virtuosity.

This is true of the way I was trained and how I trained my apprentices. While helping each other, we also try to outdo each other, showing the best we can do. Yes, there are rivalries and tensions, we share commonalities but have prior individual histories and current personal interests. We have singular voices. We are like a jazz ensemble: leading, echoing, backing each other up, letting each other go.

Today, regional group aesthetics have been supplanted by individualism - potters learn in other ways in other places and make wares reflective of other interests. Furthermore, customers seek variety. North Carolina has adapted. In Seagrove, for instance, different styles abound, making the local tradition a much-loved anomaly.

As a young man the differences between the industrial milieu in which I was raised and the artisanal seemed oppositional. As I grow older, I embrace their contradictions and find reconciliation. I love all sort of pots; I am a potter because we are potters.

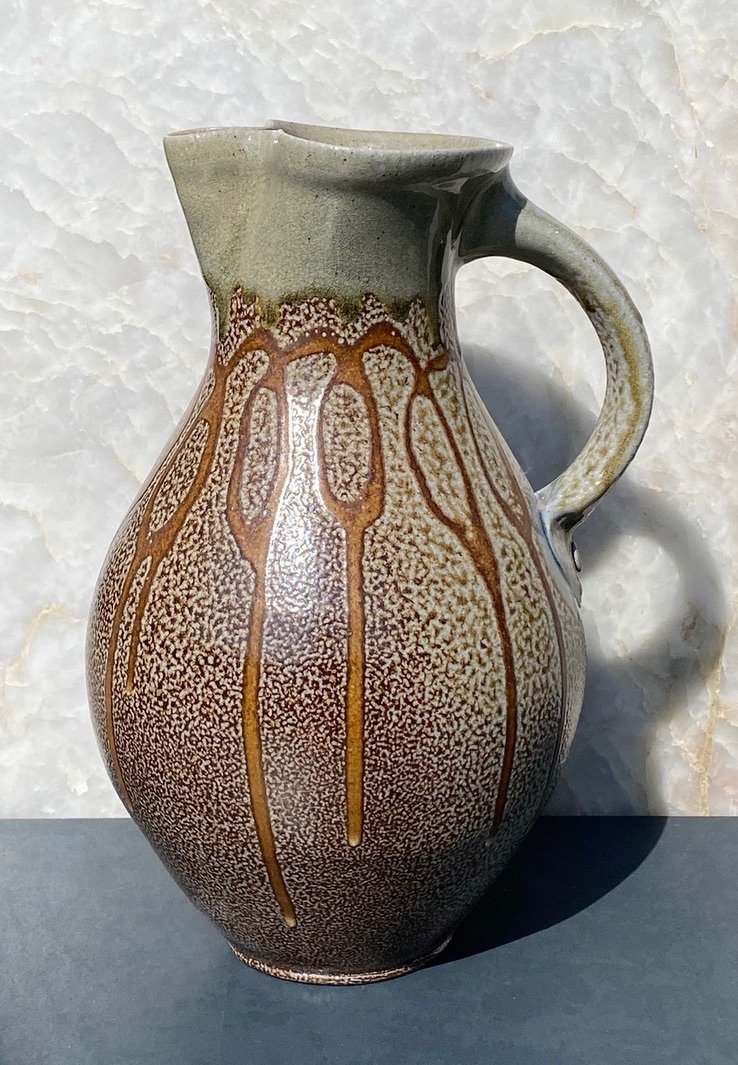

I remain devoted to creating simple useful pots, improvising on old melodies, making mugs that carry the weight of the world.

I dedicate this exhibition to my wife, Carol, and my father, Gordon Hewitt, former Director of Sales at Spode Ltd.

ARTIST BIO

Mark Hewitt comes from a ceramic upbringing, albeit an industrial one. His grandfather was CEO of Spode, the renowned English fine china manufacturer, and his father was Director of International Sales. Groomed to follow in their footsteps, Hewitt rebelled and sought an apprenticeship with the celebrated English studio potter, Michael Cardew where he apprenticed for three years. Then followed two years with a former Cardew student, Todd Piker, who had set up Cornwall Bridge Pottery in Northwest CT. While there Hewitt met his future wife, Carol, and together they moved to Pittsboro, NC where he set up his own pottery in 1983. Hewitt’s aesthetic includes the use of local clays and glaze materials, and firing his pots in a large wood burning kiln, about the size of a school bus, 35’ long, 9’ wide and 6’ tall.

Earlier travels had taken Hewitt to West Africa and Southeast Asia to study ceramic traditions there. Hewitt has been pivotal in identifying the key elements of the North and South Carolina traditions and fusing them into a vibrant and influential contemporary style, incorporating all those varied international influences. His creative outpouring of vibrant, elegant, useful pots has attracted a large and loyal clientele.

“Traditional folk pots are a type of landscape painting,” says Hewitt. “They are an echo of a place and time, reverberating with a region’s geology and cultural history.” Illustrative of this was the magnificent recent show, “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Edgefield, South Carolina,” at the Met and Boston MFA, and the University of Michigan Museum of Art. Just as the South’s famed heritage of Blues, jazz, gospel, rockabilly, and bluegrass continue to feed and inspire modern musicians, so too does North Carolina’s stubborn and multilayered pottery history provide a fertile creative base for the new works being shown “Thrown Together.”

As veteran potter and poet, Jack Troy, says, “If North America has a 'pottery state,' it must be North Carolina.” Several traditions are associated with the state, notably Moravian earthenware, the Eastern Piedmont salt glaze, the Alkaline glaze tradition from the Catawba Valley, and Art Ware made between the wars. An unbroken tradition which began in the late 18th century continues in North Carolina, and during the last forty years Hewitt and his apprentices have coalesced to reimagine a venerable tradition. Together they have realigned North Carolina folk pottery to include elements from the Mingei Movement (the Japanese Folk Art Movement), contemporary studio pottery, and industrial practice. “Thrown Together” examines the relationship between tradition and individualism, and the way apprenticeship influences future aesthetic choices.

Author and critic, Chris Benfey, compares Hewitt’s journey to that of fellow Englishman, Eric Clapton. “Crossroads: Clapton and his mates, listen to old records by Southern bluesmen from the 1930’s and come up with music utterly new and fresh, where you can feel the crossing in your bones of two traditions – rural and urban, African American and alienated European, soft and very, very loud - in creative tension. Or a young lad named Mark Hewitt, from Staffordshire, the “Potteries'' in the English Midlands, listens to the music of Southern potters and comes up with his own distinctive kind of ceramic music, utterly new and fresh – and very, very big.”

In 1982, on a road trip through the South, Hewitt visited the few remaining folk potters in Tennessee, Georgia, and North Carolina, as if searching for old Southern musicians. “I remember Lanier Meaders’ workshop in northern Georgia - eight cedar posts wrapped with tar paper, rafters made of tree limbs, and a tin roof. Then, in the Catawba Valley of North Carolina, I recall standing on Burlon Craig’s clay pile, dug just down the road, and peering into his low-slung wood burning ‘groundhog’ kiln, thinking these potteries were like Cardew’s, rooted in usefulness and locality, but raw, and unvarnished.” Visiting Art Ware era, Jugtown Pottery, near Seagrove, founded in 1921 (and still going strong,) and seeing the old Carolina crocks and jugs in the small museum at the Seagrove Pottery run by Walter and Dorothy Auman, confirmed the area’s suitability as a location for a pottery.

In addition to making pots Hewitt has curated two major exhibitions about Southern pottery, “The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery,” at the North Carolina Museum of Art, in 2005, and “Great Pots from the Traditions of North & South Carolina,” at the North Carolina Pottery Center in Seagrove, NC, where he was Board President for several years. Hewitt says, “Regional pottery traditions are like rare wildflowers that only grow in particular places. It’s a pleasure to tend these Carolina roots and see them bloom again.”

LINKS

https://hewittpottery.com

https://www.instagram.com/markhewittpottery/

https://www.facebook.com/mark.hewitt.9469